Cost-Benefit Analysis Definition

Cost-Benefit Analysis Definition

Opportunity costs—the costs associated with choosing a particular policy over an alternative policy—can also be estimated. B/C analysis provides a key piece of information that may be used in analyzing and prioritizing projects, but it is not the only information that should be considered. Hard-to-capture benefits, such as improvements in community livability, changes in housing values, or impacts to disadvantaged communities, may be difficult to fully assess in the analysis. Further, other project prioritization considerations such as political will and public acceptability will not be captured in the analysis, yet may still play a role in determining the eventual prioritization of the projects being considered for investment. Therefore, it is critical that the results of the B/C analysis be carefully combined with other nonquantifiable inputs in making final decisions regarding the relative effectiveness of various projects.

If the BCR is equal to 1.0, the ratio indicates that the NPV of expected profits equals the costs. If a project's BCR is less than 1.0, the project's costs outweigh the benefits, and it should not be considered. A benefit-cost ratio (BCR) is an indicator showing the relationship between the relative costs and benefits of a proposed project, expressed in monetary or qualitative terms. Investment cost analysis involves calculating all of the expenses required to implement and operate a given program.

Depreciation is another cost that becomes a periodic expense on the income statement. Accountants charge the cost of the asset to depreciation expense over the useful life of the asset. This cost allocation approach attempts to match costs with revenues and is more reliable than attempting to periodically determine the fair market value of the asset. Costs as a business concept are useful in measuring performance and determining profitability. What follows are brief discussions of some business applications in which costs play an important role.

A benefit–cost ratio (BCR) is an indicator, used in cost–benefit analysis, that attempts to summarize the overall value for money of a project or proposal. A BCR is the ratio of the benefits of a project or proposal, expressed in monetary terms, relative to its costs, also expressed in monetary terms. A BCR takes into account the amount of monetary gain realized by performing a project versus the amount it costs to execute the project.

Gross, Operating, and Net Profit

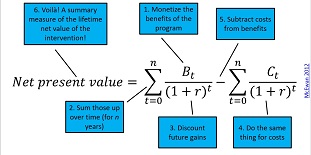

Now, the costs and benefits of the project could be accurately analyzed, and an informed decision could be made. Benefits and costs in CBA are expressed in monetary terms and are adjusted for the time value of money; all flows of benefits and costs over time are expressed on a common basis in terms of their net present value, regardless of whether they are incurred at different times.

Sales are the first line item on the income statement, and the cost of goods sold (COGS) is generally listed just below it. For example, if Company A has $100,000 in sales and a COGS of $60,000, it means the gross profit is $40,000, or $100,000 minus $60,000. Divide gross profit by sales for the gross profit margin, which is 40%, or $40,000 divided by $100,000. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. Benefit–Cost Analysis site maintained by the Transportation Economics Committee of the Transportation Research Board(TRB).

B/C analysis is defined differently, however, as the benefits and MOEs selected for any given analysis should represent the benefits accruing to users of the project as well as benefits to society at large. The real difference between these types of analyses has to do with the measures on which they focus. Economic Impact analysis focuses on measures of impact on economic indicators, such as aggregate employment or real GDP, none of which serve as a summary measure of societal benefit. Finally, depending on the particular needs of the assessment, B/C analysis may be conducted using a snapshot of traffic performance and project costs to estimate average annual benefits and costs. This average annual B/C is best used in situations where the relative benefits and costs are anticipated to be relatively stable over time.

Although CBA can offer an informed estimate of the best alternative, a perfect appraisal of all present and future costs and benefits is difficult; perfection, in economic efficiency and social welfare, is not guaranteed. Often such decisions are made through struggles between political groups, pressure groups, and interest groups (professional, public, private, and industrial). A more rational, scientific, objective, and evidence-based approach to prioritizing programs was made towards the end of the twentieth century with the use of cost–benefit analysis (CBA), where expected monetary benefits and monetary costs of interventions were compared. CBA attempts to measure the positive or negative consequences of a project.

Double-counting can occur in situations where there are overlaps in different benefits, or when a change to one benefit results in a direct change to another benefit. For example, a project to replace or upgrade traditional traffic signals to more efficient light emitting diodes (LED) signal lighting may be expected to result in a cost savings of $150,000 in electricity costs to an agency. In conducting a benefit/cost analysis of this project, the analyst should be cautious in not accounting for this impact, both as a benefit (a $150,000 gain to the agency), as well as a cost (a reduction of $150,000 in operating costs). The project prioritization process often requires more robust analysis than required during the preliminary project screening process.

- Transport Canada promoted CBA for major transport investments with the 1994 publication of its guidebook.

- Sensitivity or "what if" analysis is the act of going back in to your cost-benefit analysis and playing around with your assumptions.

- Managers and departments are then evaluated on the basis of costs and those elements of production they are expected to control.

- Controversy can sometimes be avoided by using the related technique of cost–utility analysis, in which benefits are expressed in non-monetary units such as quality-adjusted life years.

The use of CBA in the regulatory process continued under the Obama administration, along with the debate about its practical and objective value. Some analysts oppose the use of CBA in policy-making, and those in favor of it support improvements in analysis and calculations. The concept of CBA dates back to an 1848 article by Jules Dupuit, and was formalized in subsequent works by Alfred Marshall. Jules Dupuit pioneered this approach by first calculating "the social profitability of a project like the construction of a road or bridge" In an attempt to answer this, Dupuit began to look at the utility users would gain from the project.

Customer satisfaction, the value of a name brand, and even the morale of your employees are all intangible benefits. Policy analysis is important in modern complex societies, which typically have vast numbers of public policies and sophisticated and often interconnected challenges, such that public policies have tremendous social, economic, and political implications. Moreover, public policy is a dynamic process, operating under changing social, political, and economic conditions. Policy analysis helps public officials understand how social, economic, and political conditions change and how public policies must evolve in order to meet the changing needs of a changing society. It can be difficult in developing the B/C analysis framework to decide if particular impacts represent a new benefit (to users, society or the agency), or if the impacts represent a transfer of benefits from one group to another.

Induced Impacts are related to the multiplicative affects of the re-spending of new income within the region, resulting from increased regional production or employment. Indirect and induced impacts are considered in economic impact analysis, which considers these broader regional economic impacts as shown in Table 2-3. Benefit/cost analysis is often confused with Economic Impact Analysis, which serves to identify and monetize the full potential regional or national level economic benefits of a project, including changes in regional productivity, employment, and income.

Where there is a budget constraint, the ratio of NPV to the expenditure falling within the constraint should be used. In practice, the ratio of present value (PV) of future net benefits to expenditure is expressed as a BCR. (NPV-to-investment is net BCR.) BCRs have been used most extensively in the field of transport cost–benefit appraisals. ] countries refers to the BCR as the cost–benefit ratio, but this is still calculated as the ratio of benefits to costs. These criticisms continued under the Clinton administration during the 1990s.

However, as the scale of the business grows (e.g. output, number people employed, number and complexity of transactions) then more resources are required. If production rises suddenly then some short-term increase in warehousing and/or transport may be required. In these circumstances, we say that part of the cost is variable and part fixed.

The soft exercise identified and described qualitatively non-monetisable impacts, leading to option ranking. In 2005 the UK Government undertook a value for money analysis of Government investment in different types of childcare. The choice was between higher cost "integrated" childcare centres, providing a range of services to both children and parents, or lower cost "non-integrated" centres that provided basic childcare facilities.

Where decisions are mission-critical, or large sums of money are involved, other approaches – such as use of Net Present Values and Internal Rates of Return – are often more appropriate. The cost-benefit analysis does not touch on these issues and is, at best, an inexact analysis technique. The importance of cost-benefit analysis in project management is clear, but it works best when you have all the financial projections and data. Including intangible items within the analysis inevitably brings more subjectivity into the process. The final step is to compare the total costs against the total benefits and make your decision.

The guiding principle for monetizing impacts is the willingness of those affected to pay to obtain or avoid the impacts. Analysts have developed a variety of methods for predicting willingness to pay, ranging from drawing on preferences revealed by observable behavior in markets at one extreme to preferences about public goods elicited from surveys of relevant populations at the other. These methods allow analysts to estimate the net benefits of proposed policies relative to current policy. Among all the policies with positive net benefits, the set with the largest net benefits maximizes efficiency. currently am involved to look benefit cost ratio on a project concerning avocado production activities especially to the youth around mbeya-rungwe district.

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is traditionally based on conventional welfare economics, which provides a utilitarian account of value which relies on individual self-interest. In practice, people express preferences for a much wider set of public goals. Techniques such as CBA rarely give proper recognition to these wider public preferences. Consideration should be given therefore to the prevailing understanding of the public good and how this is best served. Cost-benefit analysis should normally be undertaken for any project which involves policy development, capital expenditure, use of assets or setting of standards.

Gross profit looks at profitability after direct expenses, and operating profit looks at profitability after operating expenses. If Company A has $20,000 in operating expenses, the operating profit is $40,000 minus $20,000, equaling $20,000. Divide operating profit by sales for the operating profit margin, which is 20%. The first level of profitability is gross profit, which is sales minus the cost of goods sold.

The private-sector cost of the transponder purchase may be included in the overall project cost value used in the B/C analysis. For example, a project that results in a reduction in the number of fatality crashes would clearly be a benefit to the users of the project, as they would be able to directly reduce the risk of pain and suffering for themselves and their families. Society at large could also be expected to benefit, however, from the reduction in fatality crashes. Therefore, there are broader societal benefits, in addition to the user benefit, that may accrue from a project that reduces the number of fatality crashes.

Комментарии

Отправить комментарий